-40%

RARE AUTHENTIC 18TH CENTURY JAPANESE WOODBLOCK PRINT BY ARTIST SUZUKI HARUNOBU

$ 263.99

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

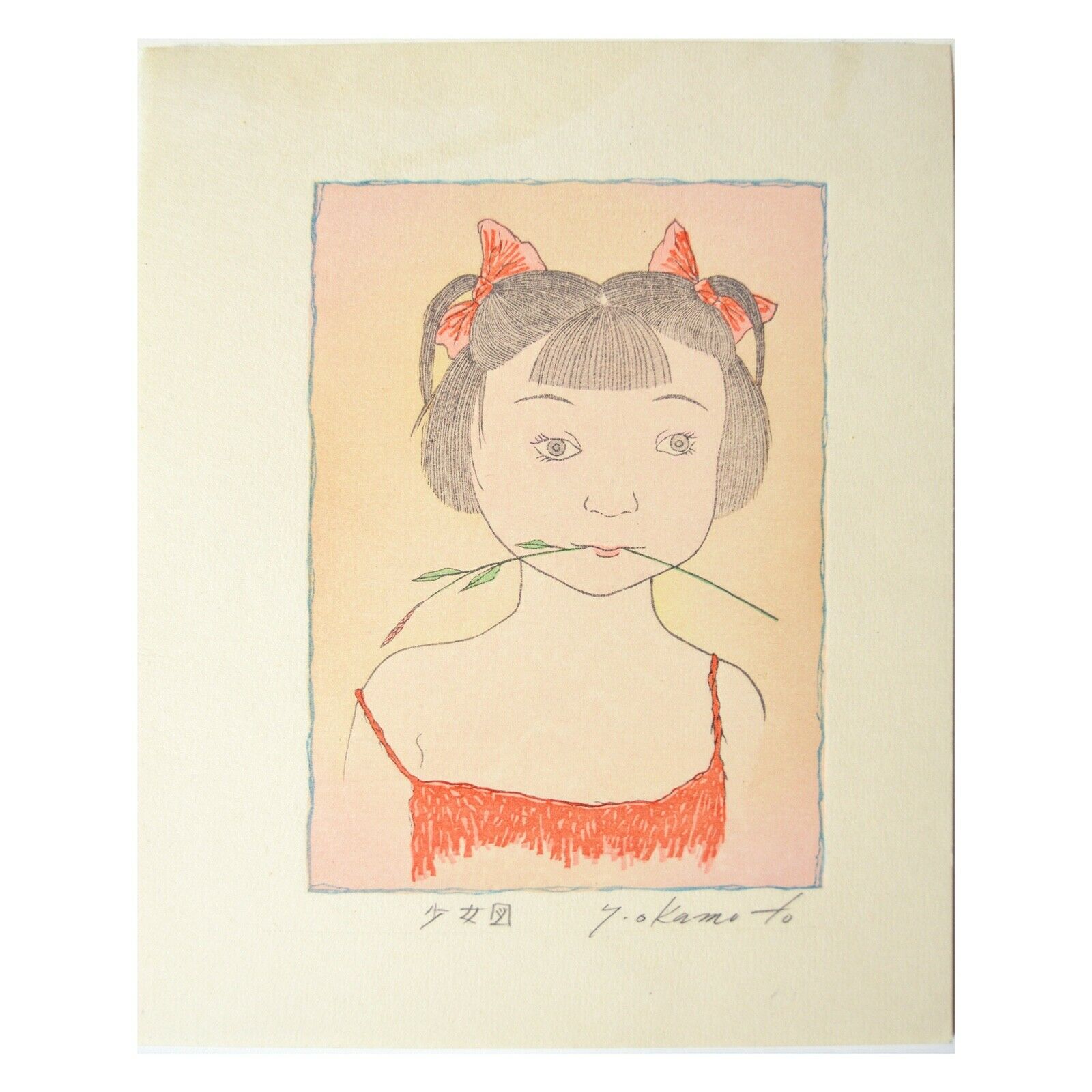

RARE AUTHENTIC "18TH CENTURY JAPANESE WOODBLOCK PRINT BY ARTIST SUZUKI HARUNOBU".PURCHASED A COLLECTION

OF "RYERSON LIBRARY ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO" ART STUDY BOARDS FROM THE 1930'S AND 40'S THAT HAD BEEN SOLD TO A COLLECTOR SOMETIME IN THE EARLY 1950'S AND THEN PURCHASED BY ME IN HIS ESTATE SALE. THE FAMOUS "ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO RYERSON LIBRARY" HOUSED AUTHENTIC FINE ART FOR THE PUBLIC TO COME AND VIEW AND STUDY BACK THEN AS IT IS TODAY. IN THE 1930'S 40'S THEY WOULD MOUNT ACTUAL AUTHENTIC PAPER AND SMALL PAINTINGS ESPECIALLY ASIAN ART ON THESE LARGE THICK CARDBOARD CARDS AND CATALOG AND FILE THEM GIVING THE PUBLIC EASY ACCESS TO THEM LIKE IN A FILE CABINET STYLE. AT THIS EARLY TIME PERIOD THE INSTITUTE WAS NOT VERY "CONSERVATION CONSCIENCE" ESPECIALLY FOR THEIR SMALLER PAPER ART, WATERCOLOR PAINTINGS AND SOME FOREIGN ART, ETC. AND WOULD LIKE THIS FINE JAPANESE WOODBLOCK PRINT SIMPLY PASTE IT ON THEIR STUDY BOARDS.

MEASURING 11 X 8.6 INCHES. (

WHILE I AM FAIRLY KNOWLEDGEABLE ABOUT JAPANESE WOODBLOCK PRINTS AND DO KNOW THAT THIS IS A TRUE ANTIQUE WOODBLOCK PRINT BY THE FEEL OF THE INDENTATIONS IN THE PAPER AND HOW THE COLOR IS LAYED OUT ON THE SURFACE, ETC., YOU WILL HAVE TO DETERMINE IF IT IS A TRUE 18TH CENTURY PRINT DONE DURING THE ARTISTS LIFE TIME. IT IS VERY ACCURATE BUT I CANNOT TELL SO BUYER BEWARE).

THE ARTIST HISTORY IS WRITTEN BELOW TO READ:

PLEASE READ MY "CONDITION REPORT" AND LOOK OVER ALL MY PICTURES BEFORE DOING ANY BIDDING.

THIS AUCTION WILL CONTINUE TELL ITS END WITHOUT A "BUY IT NOW" PRICE - SO PLEASE DO NOT EMAIL ME WITH OFFERS.

PLEASE DO NOT BID ON MY AUCTIONS IF YOU ARE NOT INTENDING TO PAY FOR YOUR

HIGH BID AMOUNT!

THANK YOU AND ENJOY THE AUCTION!

Suzuki Harunobu

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

In this

Japanese name

, the

surname

is

Suzuki

.

Two girls

,

c.

1750

Suzuki Harunobu

(

Japanese

:

鈴木 春信

;

c.

1725 – 8 July 1770

) was a Japanese designer of

woodblock print

art in the

ukiyo-e

style. He was an innovator, the first to produce full-color prints (

nishiki-e

) in 1765, rendering obsolete the former modes of two- and three-color prints. Harunobu used many special techniques, and depicted a wide variety of subjects, from classical poems to

contemporary beauties

. Like many artists of his day, Harunobu also produced a number of

shunga

, or erotic images. During his lifetime and shortly afterwards, many artists imitated his style. A few, such as

Harushige

, even boasted of their ability to forge the work of the great master. Much about Harunobu's life is unknown.

Influences

[

edit

]

Young Man Playing Flute

Sexual misconduct

, from the book

Fashionable, Lusty

Mane'emon

, 1770,

Honolulu Museum of Art

Though some scholars assert that Harunobu was originally from

Kyoto

, pointing to possible influences from

Nishikawa Sukenobu

, much of his work, in particular his early work, is in the

Edo

style. His work shows evidence of influences from many artists, including

Torii Kiyomitsu

,

Ishikawa Toyonobu

, the

Kawamata school

, and the

Kanō school

. However, the strongest influence upon Harunobu was the painter and printmaker

Nishikawa Sukenobu

, who may have been Harunobu's direct teacher.

Artistic career

[

edit

]

Little is known of Harunobu's early life; his birthplace and birthdate are unknown, but it is believed he grew up in Kyoto. It is said he was 46 at his death in 1770. Unlike most

ukiyo-e

artists, Harunobu used his real name rather than an artist name. He was from a

samurai

family, and had an ancestor who was a retainer of

Tokugawa Ieyasu

in

Mikawa Province

; this Suzuki accompanied Ieyasu to Edo when the latter had his capital built there. Harunobu's grandfather Shigemitsu and father Shigekazu were stripped of their

hatamoto

status when they were found to be involved in financing of gambling and other activities; they were exiled from Edo and relocated to Kyoto. At some point, Harunobu became a student of the

ukiyo-e

master

Nishikawa Sukenobu

.

[1]

Harunobu began his career in the style of the

Torii school

, creating many works which, while skillful, were not innovative and did not stand out. It was only through his involvement with a group of

literati

samurai that Harunobu tackled new formats and styles.

In 1764, as a result of his social connections, he was chosen to aid these samurai in their amateur efforts to create

e-goyomi

[

ja

]

. Calendars prints of this sort from prior to that year are not unknown but are quite rare, and it is known that Harunobu was close acquaintances or friends with many of the prominent artists and scholars of the period, as well as with several friends of the

shōgun

. Harunobu's calendars, which incorporated the calculations of the lunar calendar into their images, would be exchanged at Edo gatherings and parties.

These calendar prints would be the very first

nishiki-e

(brocade prints). As a result of the wealth and connoisseurship of his samurai patrons, Harunobu exclusively created these prints using the best materials available. Harunobu experimented with better woods for the woodblocks, using

cherry

wood instead of

catalpa

, and used not only more expensive colors, but also a thicker application of the colors, in order to achieve a more opaque effect.

The most important of Harunobu's innovationa in the creation of

nishiki-e

was the use of multiple separate wood blocks in the creation of a single image, an expense afforded through the wealth of his clients. Just 20 years previously, the invention of

benizuri-e

had made it possible to print in three or four colors; Harunobu applied tis new technique to

ukiyo-e

prints using up to ten different colors on a single sheet of paper. The new technique depended on using notches and wedges to hold the paper in place and keep the successive color printings in register. Harunobu was the first

ukiyo-e

artist to consistently use more than three colors in each print.

Nishiki-e

, unlike their predecessors, were full-color images. As the technique was first used in a calendar, the year of their origin can be traced precisely to 1765.

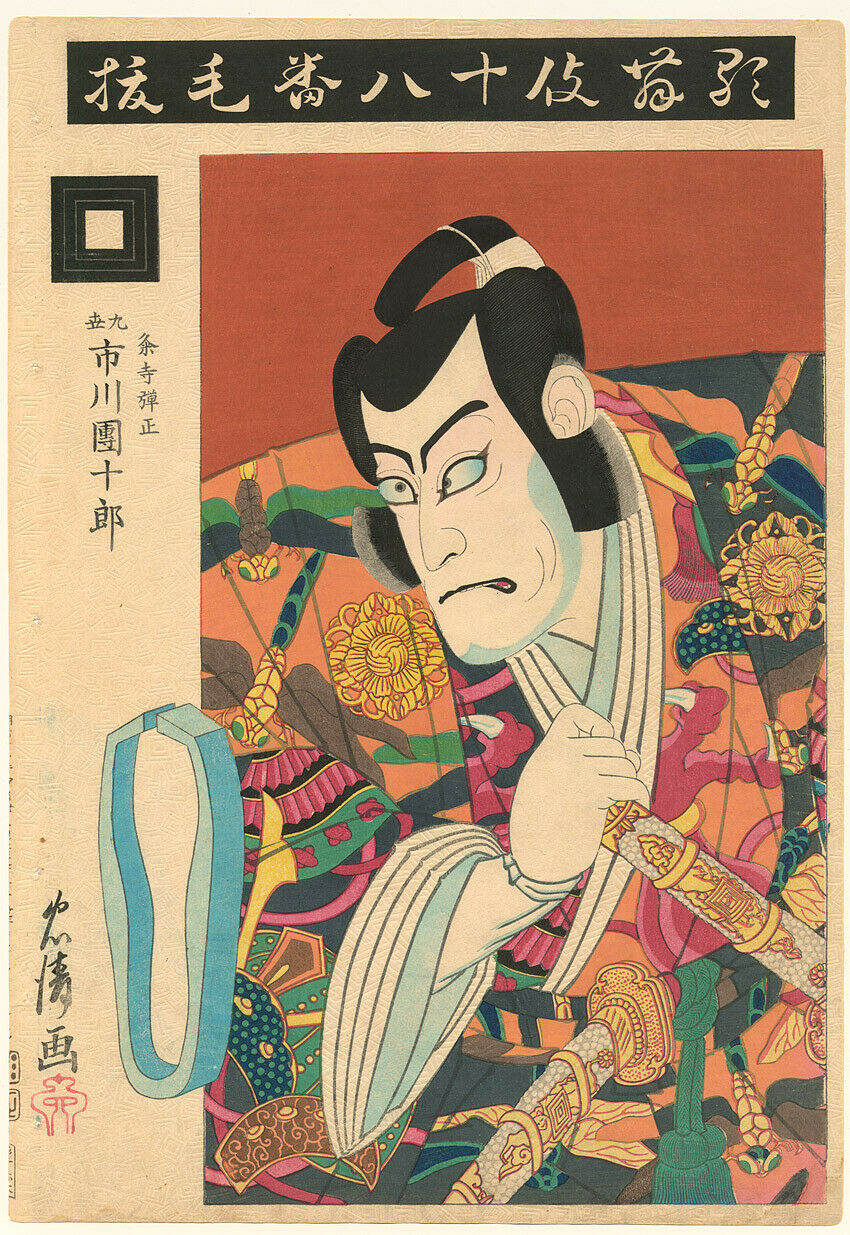

In the late 1760s, Harunobu thus became one of the primary producers of images of

bijin-ga

(pictures of beautiful women), actors of Edo and related subjects for the Edo print connoisseur market; however, he did not produce prints of

kabuki

actors, reported to have said, "Why should I paint pictures of such trash as Kabuki actors".

[2]

In a few special cases, notably his famous set of eight prints entitled

Zashiki hakkei

(Eight Parlor Views), the patron's name appears on the print along with, or in place of, Harunobu's own. The presence of a patron's name or seal, and especially the omission of that of the artist, was another novel development in

ukiyo-e

of this time.

Between 1765 and 1770, Harunobu created over twenty

illustrated books

and over one thousand color prints, along with a number of paintings. He came to be regarded as the master of

ukiyo-e

during these last years of his life, and was widely imitated until, a number of years after his death, his style was eclipsed by that of new artists, including

Katsukawa Shunshō

and

Torii Kiyonaga

.